The most terrible concentration camps of Nazi Germany. Photo

The journey from Berlin Tegel Airport to Ravensbrück takes just over an hour. In February 2006, when I first came here, there was heavy snow and a truck crashed on the Berlin ring road, so the journey took longer.

Heinrich Himmler often traveled to Ravensbrück, even in such ferocious weather. The head of the SS had friends living in the vicinity, and if he passed by, he would drop by for an inspection of the camp. He rarely left without issuing new orders. One day he ordered more root vegetables to be put into the prisoners' soup. And another time he was indignant that the extermination of prisoners was happening too slowly.

Ravensbrück was the only Nazi concentration camp for women. The camp takes its name from a small village outside the town of Fürstenberg and is located approximately 80 km north of Berlin along the road leading to the Baltic Sea. Women entering the camp at night sometimes thought they were near the sea because they could smell the salt in the air and feel the sand under their feet. But when dawn broke, they realized that the camp was located on the shore of a lake and surrounded by forest. Himmler liked to locate camps in hidden places with beautiful nature. The view of the camp is still hidden today; the heinous crimes that took place here and the courage of its victims are still largely unknown.

Ravensbrück was created in May 1939, just four months before the start of the war, and was liberated by Soviet soldiers six years later - one of the last camps to be reached by the Allies. In its first year it housed fewer than 2,000 prisoners, almost all of them German. Many were arrested because they opposed Hitler - for example, communists, or Jehovah's Witnesses who called Hitler the Antichrist. Others were imprisoned because the Nazis considered them inferior beings whose presence in society was undesirable: prostitutes, criminals, beggars, gypsies. Later, the camp began to house thousands of women from Nazi-occupied countries, many of whom took part in the Resistance. Children were also brought here. A small proportion of the prisoners - about 10 percent - were Jews, but the camp was not officially intended only for them.

Ravensbrück's largest prison population was 45,000 women; During the more than six years of the camp's existence, approximately 130,000 women passed through its gates, being beaten, starved, forced to work until death, poisoned, tortured, and killed in gas chambers. Estimates of the number of casualties range from 30,000 to 90,000; the real number most likely lies between these figures - too few SS documents have survived to say for sure. The massive destruction of evidence at Ravensbrück is one of the reasons why so little is known about the camp. In the last days of its existence, the files of all prisoners were burned in the crematorium or at the stake, along with their bodies. The ashes were thrown into the lake.

I first learned about Ravensbrück while writing my earlier book about Vera Atkins, a Special Operations Executive intelligence officer during World War II. Immediately after her graduation, Vera began an independent search for women from the USO (British Special Operations Executive - approx. Newwhat), who parachuted into occupied French territory to help the Resistance, many of whom were reported missing. Vera followed their trail and discovered that some of them had been captured and placed in concentration camps.

I tried to reconstruct her search and began with personal notes kept in brown cardboard boxes by her half-sister Phoebe Atkins at their home in Cornwall. The word "Ravensbrück" was written on one of these boxes. Inside were handwritten interviews with survivors and suspected SS members - some of the first evidence received about the camp. I leafed through the papers. “They forced us to undress and shaved our heads,” one of the women told Vera. There was a "pillar of choking blue smoke."

Vera Atkins. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Vera Atkins. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

One survivor spoke of a camp hospital where “the bacteria that causes syphilis was injected into the spinal cord.” Another described the women's arrival at the camp after the death march from Auschwitz, through the snow. One SOE agent imprisoned in the Dachau camp wrote that he had heard of women from Ravensbrück being forced to work in the Dachau brothel.

Several people mentioned a young female security guard named Binz with "short blonde hair." Another matron was once a nanny in Wimbledon. Among the prisoners, according to the British investigator, were the “cream of European women’s society,” including the niece of Charles de Gaulle, a former British golf champion and many Polish countesses.

I started looking up dates of birth and addresses, in case any of the survivors - or even the guards - were still alive. Someone gave Vera the address of Mrs. Shatne, who “knew about the sterilization of children in Block 11.” Dr. Louise le Port compiled a detailed report, which indicated that the camp was built on land owned by Himmler, and his personal residence was nearby. Le Port lived at Merignac, Gironde, but judging by her date of birth, she was already dead by that time. A Guernsey woman, Julia Barry, lived in Nettlebed, Oxfordshire. The Russian survivor allegedly worked “at the mother and child center at the Leningradsky railway station.”

On the back wall of the box I found a handwritten list of prisoners, taken away by a Polish woman who took notes in the camp and also drew sketches and maps. “The Poles were better informed,” the note says. The woman who compiled the list was most likely long dead, but some of the addresses were in London and those who escaped were still alive.

I took these sketches with me on my first trip to Ravensbrück, in the hope that they would help guide me when I got there. However, due to the snow piles on the road, I doubted whether I would get there at all.

Many tried to get to Ravensbrück, but could not. Representatives of the Red Cross tried to get to the camp in the chaos of the last days of the war, but were forced to turn back, so huge was the flow of refugees moving towards them. A few months after the end of the war, when Vera Atkins chose this road to begin her investigation, she was stopped at a Russian checkpoint; the camp was located in the Russian zone of occupation and access to citizens of allied countries was closed. By this time, Vera's expedition had become part of the larger British investigation into the camp, which resulted in the first Ravensbrück war crimes trials, beginning in Hamburg in 1946.

In the 1950s, as the Cold War began, Ravensbrück disappeared behind the Iron Curtain, dividing survivors from the east and west and splitting the camp's history in two.

In Soviet territories, this site became a memorial to communist camp heroines, and all streets and schools in East Germany were named after them.

Meanwhile, in the West, Ravensbrück literally disappeared from view. Former prisoners, historians and journalists could not get even close to this place. In their countries, former prisoners fought to have their stories published, but it proved too difficult to obtain evidence. The transcripts of the Hamburg Tribunal were hidden under the heading “secret” for thirty years.

“Where was he?” was one of the most common questions I was asked when I started my book on Ravensbrück. Along with “Why was a separate women’s camp needed? Were these women Jewish? Was it a death camp or a work camp? Are any of them alive now?

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In the countries that lost the most people in the camp, groups of survivors tried to preserve the memory of what happened. Approximately 8,000 French, 1,000 Dutch, 18,000 Russians and 40,000 Poles were imprisoned. Now, in each country - for various reasons - this story is being forgotten.

The ignorance of both the British - who only had about twenty women in the camp - and the Americans is truly frightening. Britain may know about Dachau, the first concentration camp, and perhaps about the Bergen-Belsen camp, since British troops liberated it and captured the horror they saw in images that forever traumatized the British consciousness. Another thing is with Auschwitz, which became synonymous with the extermination of Jews in gas chambers and left a real echo.

After reading the materials collected by Vera, I decided to look at what had been written about the camp. Popular historians (almost all of whom were men) had little to say. Even books written after the end of the Cold War seemed to describe an entirely masculine world. Then a friend of mine working in Berlin shared with me a substantial collection of essays written primarily by German women scientists. In the 1990s, feminist historians began to respond. This book aims to liberate women from the anonymity that the word "prisoner" implies. Many further studies, often German, were built on the same principle: the history of Ravensbrück was viewed too one-sidedly, which seemed to drown out all the pain of the terrible events. One day I happened to come across mentions of a certain “Book of Memory” - it seemed to me something much more interesting, so I tried to contact the author.

More than once I came across the memoirs of other prisoners published in the 1960s and 70s. Their books gathered dust in the depths of public libraries, although many of the covers were extremely provocative. The cover of the memoirs of French literature teacher Micheline Morel showed a gorgeous, Bond girl-style woman thrown behind barbed wire. The book about one of the first matrons of Ravensbrück, Irma Grese, was called The Beautiful Beast(“Beautiful Beast”). The language of these memoirs seemed outdated and far-fetched. Some described the guards as “lesbians with a brutal look,” others drew attention to the “savagery” of the German prisoners, which “gave reason to reflect on the basic virtues of the race.” Such texts were confusing, and it seemed as if neither author knew how to put a story together well. In the preface to one of the collections of memoirs, the famous French writer Francois Mauriac wrote that Ravensbrück became “a shame that the world decided to forget.” Perhaps I'd better write about something else, so I went to meet Yvonne Baseden, the only survivor I had information about, to get her opinion.

Yvonne was one of the women in the USO unit led by Vera Atkins. She was caught while helping the Resistance in France and sent to Ravensbrück. Yvonne was always willing to talk about her work in the Resistance, but as soon as I brought up the topic of Ravensbrück, she immediately “knew nothing” and turned away from me.

This time I said that I was going to write a book about the camp, and I hoped to hear her story. She looked up at me in horror.

"Oh no, you can't do that."

I asked why not. “This is too terrible. Can't you write about something else? How are you going to tell your kids what you do?”

Didn't she think this story needed to be told? "Oh yeah. Nobody knows anything at all about Ravensbrück. No one has wanted to know since our return.” She looked out the window.

As I was about to leave, she gave me a small book - another memoir, with a particularly terrifying cover of intertwined black and white figures. Yvonne had not read it, she said, insistently handing the book to me. It looked like she wanted to get rid of it.

At home I discovered another one, blue, under a frightening cover. I read the book in one sitting. The author was a young French lawyer named Denise Dufournier. She was able to write a simple and touching story of the struggle for life. The “abomination” of the book was not only that the history of Ravensbrück was forgotten, but also that everything actually happened.

A few days later I heard French in my answering machine. The speaker was Doctor Louise le Port (currently Liard), a doctor from the city of Merignac, whom I had previously considered dead. However, now she invited me to Bordeaux, where she lived then. I could stay as long as I wanted because we had a lot to discuss. “But you should hurry. I am 93 years old".

Soon I contacted Bärbel Schindler-Zefkow, author of The Book of Memory. Bärbel, the daughter of a German communist prisoner, compiled a "database" of prisoners; she traveled for a long time in search of lists of prisoners in forgotten archives. She gave me the address of Valentina Makarova, a Belarusian partisan who survived Auschwitz. Valentina answered me, offering to visit her in Minsk.

By the time I reached the suburbs of Berlin, the snow had begun to fade. I drove past the sign for Sachsenhausen, where the concentration camp for men was located. This meant that I was moving in the right direction. Sachsenhausen and Ravensbrück were closely connected. In the men's camp they even baked bread for the women prisoners, and every day it was sent to Ravensbrück along this road. At first, each woman received half a loaf every evening. By the end of the war, they were given barely more than a thin morsel, and the “useless mouths,” as the Nazis called those they wanted to get rid of, received nothing at all.

SS officers, guards and prisoners regularly moved from one camp to another as Himmler's administration tried to make the most of resources. At the beginning of the war, a women's department was opened in Auschwitz, and then in other men's camps, and female guards were trained in Ravensbrück, who were then sent to other camps. Towards the end of the war, several high-ranking SS officers were sent from Auschwitz to Ravensbrück. Prisoners were also exchanged. Thus, despite the fact that Ravensbrück was an all-female camp, it borrowed many of the features of male camps.

The SS empire created by Himmler was enormous: by mid-war there were at least 15,000 Nazi camps, including temporary work camps, as well as thousands of satellite ones associated with the main concentration camps scattered throughout Germany and Poland. The largest and most horrific were the camps built in 1942 as part of the Final Solution. It is estimated that 6 million Jews were killed by the end of the war. Today, the facts about the genocide of the Jews are so well known and so staggering that many believe that Hitler's extermination program was all about the Holocaust.

People interested in Ravensbrück are usually very surprised to learn that most of the women imprisoned there were not Jewish.

Today, historians distinguish between different types of camps, but these names can be confusing. Ravensbrück is often defined as a "slave labor" camp. This term is intended to soften the horror of what happened, and could also be one of the reasons why the camp was forgotten. Certainly, Ravensbrück became an important part of the slave labor system - Siemens, the electronics giant, had factories there - but labor was just a stage on the road to death. Prisoners called Ravensbrück a death camp. A French survivor, ethnologist Germaine Tillon, said the people there were “slowly destroyed.”

Photo: PPCC Antifa

Moving away from Berlin, I observed white fields that gave way to dense trees. From time to time I drove past abandoned collective farms left over from communist times.

In the depths of the forest, the snow was falling more and more heavily, and it became difficult for me to find the road. Women from Ravensbrück were often sent into the forest to cut down trees during snowfall. The snow stuck to their wooden shoes, so that they walked on a kind of snow platforms, their legs twisted. If they fell, German shepherds, led nearby on leashes by guards, would rush at them.

The names of the villages in the forest were reminiscent of those that I read about in the testimony. From the village of Altglobzo came Dorothea Binz, a matron with short hair. Then the spire of the Fürstenberg Church appeared. The camp was not visible from the city center, but I knew that it was on the other side of the lake. Prisoners told how, leaving the gates of the camp, they saw a spire. I passed Fürstenberg station, where so many terrible journeys have ended. One February night, women of the Red Army arrived here, brought from Crimea in cattle cars.

Dorothea Binz at the first Ravensbrück trial in 1947. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On the other side of Fürstenberg, a cobblestone road built by the prisoners led to the camp. On the left side were houses with gable roofs; Thanks to Vera’s map, I knew that guards lived in these houses. In one of the houses there was a hostel where I was going to spend the night. The interior of the previous owners has long been replaced with impeccable modern furnishings, but the spirits of the wardens still live in their old rooms.

On the right side there was a view of the wide and snow-white surface of the lake. Ahead was the commandant's headquarters and a high wall. A few minutes later I was already standing at the entrance to the camp. Ahead was another wide white field, planted with linden trees, which, as I later learned, were planted in the early days of the camp. All the barracks that were located under the trees disappeared. During the Cold War, the Russians used the camp as a tank base and demolished most of the buildings. Russian soldiers played football on what was once called Appelplatz and where prisoners stood for roll call. I had heard about the Russian base, but I didn't expect to find such a level of destruction.

The Siemens camp, located a few hundred meters from the southern wall, was overgrown and very difficult to get into. The same thing happened with the annex, the “youth camp,” where many murders were committed. I had to picture them in my mind, but I didn't have to imagine the cold. The prisoners stood here in the square for hours, wearing thin cotton clothes. I decided to take refuge in the “bunker,” a stone prison building whose cells were converted during the Cold War into memorials for the dead communists. Lists of names were carved into gleaming black granite.

In one of the rooms, workers were removing memorials and redecorating the room. Now that power had returned to the West, historians and archivists were working on a new account of the events that took place here and on a new memorial exhibition.

Outside the camp walls, I found other, more personal memorials. Next to the crematorium there was a long passage with high walls, known as "shooting alley". There was a small bouquet of roses lying here: if they had not frozen, they would have withered. There was a nameplate nearby.

Three bouquets of flowers lay on the stoves in the crematorium, and the shore of the lake was strewn with roses. Since the camp became accessible again, former prisoners have begun to come to remember their fallen friends. I needed to find other survivors while I had time.

Now I understand what my book should be: a biography of Ravensbrück from beginning to end. I have to try my best to put the pieces of this story together. The book aims to shed light on Nazi crimes against women and show how understanding what happened in women's camps can expand our knowledge of the history of Nazism.

So much evidence was destroyed, so many facts were forgotten and distorted. But still, much has been preserved, and now new indications can be found. British court records have long since returned to the public domain, and many details of those events have been found in them. Documents that were hidden behind the Iron Curtain have also become available: since the end of the Cold War, the Russians have partially opened their archives, and evidence has been found in several European capitals that had never before been examined. Survivors from the east and west sides began to share memories with each other. Their children asked questions and found hidden letters and diaries.

The voices of the prisoners themselves played the most important role in the creation of this book. They will guide me, reveal to me what really happened. A few months later, in the spring, I returned to the annual ceremony to mark the liberation of the camp and met Valentina Makarova, a survivor of the death march at Auschwitz. She wrote to me from Minsk. Her hair was white with a blue tint, her face was sharp as flint. When I asked how she managed to survive, she replied: “I believed in victory.” She said it as if I should have known it.

When I approached the room in which the executions were carried out, the sun suddenly peeked out from behind the clouds for a few minutes. Wood pigeons sang in the linden trees, as if trying to drown out the noise from cars rushing past. A bus carrying French schoolchildren was parked near the building; they crowded around the car to smoke a cigarette.

My gaze was directed to the other side of the frozen lake, where the spire of the Fürstenberg Church was visible. There, in the distance, workers were working on boats; in the summer, visitors often rent boats, not realizing that the ashes of camp prisoners lie at the bottom of the lake. The rushing wind drove a lonely red rose along the edge of the ice.

“1957. The doorbell rings, recalls Margarete Buber-Neumann, a Ravensbrück prisoner survivor. - I open it and see an elderly woman in front of me: she is breathing heavily, and several teeth are missing from her mouth. The guest mutters: “Don’t you really recognize me?” It's me, Johanna Langefeld. I was the chief overseer in Ravensbrück.” The last time I saw her was fourteen years ago, in her office at the camp. I acted as her secretary... She often prayed, asking God to give her the strength to put an end to the evil that was happening in the camp, but every time a Jewish woman appeared on the threshold of her office, her face was distorted with hatred...

And here we are sitting at the same table. She says that she would like to be born a man. He talks about Himmler, whom he still calls “Reichsführer” from time to time. She talks non-stop for several hours, gets confused about the events of different years and tries to somehow justify her actions.”

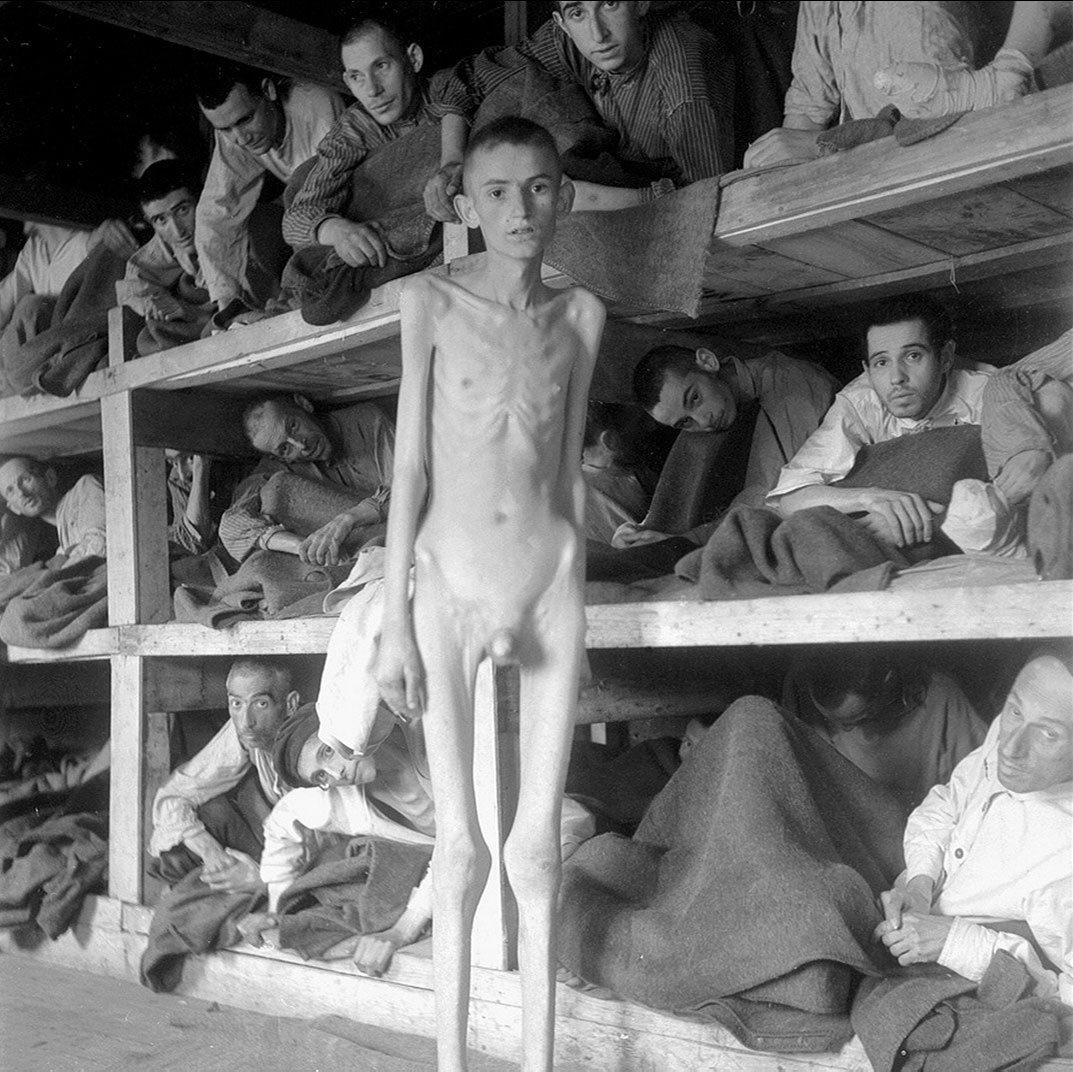

Prisoners in Ravensbrück.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

At the beginning of May 1939, a small line of trucks appeared from behind the trees surrounding the tiny village of Ravensbrück, lost in the Mecklenburg Forest. The cars drove along the shore of the lake, but their axles got stuck in the marshy coastal soil. Some of the new arrivals jumped out to dig out the cars; others began to unload the boxes they had brought.

Among them was a woman in a uniform - a gray jacket and skirt. Her feet immediately got stuck in the sand, but she quickly freed herself, climbed to the top of the slope and examined the surroundings. Behind the surface of the lake, shining in the sun, rows of fallen trees could be seen. The smell of sawdust hung in the air. The sun was blazing, but there was no shadow anywhere nearby. To her right, on the far shore of the lake, was the small town of Fürstenberg. The coast was dotted with boat houses. A church spire could be seen in the distance.

On the opposite shore of the lake, to her left, a long gray wall about 5 meters high rose up. A forest path led to the complex's iron gates, towering above the surrounding area, with "No Trespassing" signs hanging on them. The woman - of average height, stocky, with curly brown hair - purposefully moved towards the gate.

Johanna Langefeld arrived with the first batch of guards and prisoners to oversee the unloading of equipment and inspect the new concentration camp for women; it was planned that it would begin functioning in a few days, and Langefeld would become oberaufzeerin- senior supervisor. During her life she had seen many women's correctional institutions, but none of them could be compared with Ravensbrück.

A year before her new appointment, Langefeld served as senior matron at Lichtenburg, a medieval fortress near Torgau, a city on the banks of the Elbe. Lichtenburg was temporarily turned into a women's camp during the construction of Ravensbrück; crumbling halls and damp dungeons were cramped and conducive to disease; The conditions of detention were unbearable for women. Ravensbrück was built specifically for its intended purpose. The camp area was about six acres - enough to more than accommodate about 1,000 women from the first batch of prisoners.

Langefeld walked through the iron gates and walked along Appelplatz, the main square of the camp, the size of a football field, capable of housing all the camp's prisoners if necessary. Loudspeakers hung along the edges of the square, above Langefeld's head, although for now the only sound in the camp was the sound of nails being driven in from afar. The walls cut off the camp from the outside world, leaving only the sky above its territory visible.

Unlike the men's concentration camps, at Ravensbrück there were no guard towers or machine gun emplacements along the walls. However, an electric fence snaked around the perimeter of the outside wall, accompanied by skull and crossbones signs warning that the fence was high voltage. Only to the south, to the right of Lengefeld, did the surface rise enough to make out the tops of the trees on the hill.

The main building on the camp grounds were huge gray barracks. Wooden houses, erected in a checkerboard pattern, were one-story buildings with tiny windows that lined the central square of the camp. Two rows of exactly the same barracks - the only difference being a slightly larger size - were located on either side of Lagerstraße, the main street of Ravensbrück.

Langefeld examined the blocks one by one. The first was the SS dining room with brand new tables and chairs. To the left of Appelplatz there was also Revere- the Germans used this term to refer to infirmaries and medical bays. Crossing the square, she entered a sanitary block equipped with dozens of showers. Boxes of striped cotton robes were piled in a corner of the room, and at a table a handful of women laid out stacks of colored felt triangles.

Under the same roof as the bathhouse there was a camp kitchen, shining with large pots and kettles. The next building housed a warehouse for prison clothes, Effektenkammer, where heaps of large brown paper bags were stored, and then there was a laundry room, Wascherei, with six centrifugal washing machines - Langefeld would like to have more of them.

A poultry farm was being built nearby. Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS who ran concentration camps and much more in Nazi Germany, wanted his creations to be as self-sufficient as possible. In Ravensbrück, it was planned to build cages for rabbits, a chicken coop and a vegetable garden, as well as plant fruit and flower gardens, where gooseberry bushes brought from the gardens of the Lichtenburg concentration camp had already begun to be transplanted. The contents of Lichtenburg cesspools were also brought to Ravensbrück and used as fertilizer. Among other things, Himmler demanded that the camps pool resources. In Ravensbrück, for example, there were no bread ovens, so bread was brought daily from Sachsenhausen, a men's camp 80 km to the south.

The senior matron walked along Lagerstrasse (the main street of the camp, running between the barracks - approx. Newabout), which began on the far side of Appelplatz and led deep into the camp. The barracks were located along Lagerstrasse in a precise order, so that the windows of one building overlooked the back wall of the other. In these buildings, 8 on each side of the “street,” prisoners lived. The first barracks had red sage flowers planted; between the others grew linden seedlings.

As in all concentration camps, the grid layout was used at Ravensbrück primarily to ensure that prisoners were always visible, which meant fewer guards were needed. A brigade of thirty female guards and a detachment of twelve SS men were sent there - all together under the command of Sturmbannführer Max Koegel.

Johanna Langefeld believed that she could run a women's concentration camp better than any man, and certainly better than Max Kögel, whose methods she despised. Himmler, however, made it clear that the management of Ravensbrück was to rely on the principles of management of the men's camps, which meant that Langefeld and her subordinates had to report to the SS commandant.

Formally, neither she nor the other guards had anything to do with the camp. They were not simply subordinate to men - women had no rank or rank - they were only “auxiliary forces” of the SS. The majority remained unarmed, although those guarding the labor squads carried a pistol; many had service dogs. Himmler believed that women were more afraid of dogs than men.

However, Koegel's power here was not absolute. At that time, he was only an acting commandant and did not have some powers. For example, the camp was not allowed to have a special prison, or “bunker,” for troublemakers, which was the norm in men’s camps. He also could not order "official" beatings. Angered by the restrictions, the Sturmbannführer sent a request to his SS superiors for increased powers to punish prisoners, but the request was not granted.

However, Langefeld, who highly valued drill and discipline rather than beatings, was satisfied with such conditions, mainly when she was able to extract significant concessions in the day-to-day management of the camp. In the camp rule book, Lagerordnung, it was noted that the senior matron has the right to advise the Schutzhaftlagerführer (first deputy commandant) on “women’s issues,” although their content was not defined.

Langefeld looked around as she entered one of the barracks. Like many things, organizing the rest of prisoners in the camp was new to her - more than 150 women simply slept in each room; there were no separate cells, as she was used to. All buildings were divided into two large sleeping rooms, A and B, flanked on either side by washing areas, with a row of twelve bathing basins and twelve latrines, and a common day room where the prisoners ate.

The sleeping areas were filled with three-story bunks made from wooden planks. Each prisoner had a sawdust-stuffed mattress, a pillow, a sheet, and a blue-and-white-checkered blanket folded by the bed.

The value of drill and discipline was instilled in Langefeld from an early age. She was born into the family of a blacksmith under the name Johanna May, in the town of Kupferdre, Ruhr region, in March 1900. She and her older sister were raised in a strict Lutheran tradition - their parents drilled into them the importance of frugality, obedience and daily prayer. Like any good Protestant, Johanna knew from childhood that her life would be defined by the role of a faithful wife and mother: “Kinder, Küche, Kirche,” that is, “children, kitchen, church,” which was a familiar rule in her parents’ house. But from an early age, Johanna dreamed of more.

Her parents often talked about Germany's past. After church on Sunday, they recalled the humiliating occupation of their beloved Ruhr by Napoleon's troops, and the whole family knelt, praying to God to restore Germany to its former greatness. The girl's idol was her namesake, Johanna Prochaska, a heroine of the liberation wars of the early 19th century, who pretended to be a man to fight the French.

Johanna Langefeld told all this to Margarete Buber-Neumann, a former prisoner on whose door she knocked many years later, in an attempt to “explain her behavior.” Margaret, imprisoned in Ravesbrück for four years, was shocked by the appearance of the former matron on her doorstep in 1957; Neumann was extremely interested in Langefeld’s story about her “odyssey,” and she wrote it down.

In the year of the outbreak of the First World War, Johanna, who was then 14 years old, rejoiced along with the others when the Kupferdre boys went to the front to restore the greatness of Germany, until she realized that her role and the role of all German women in this matter was small. Two years later, it became clear that the end of the war would not come soon, and German women suddenly received orders to go to work in mines, offices and factories; there, deep in the rear, women had the opportunity to take on men's work, but only to be left out of work again after the men returned from the front.

Two million Germans had died in the trenches, but six million had survived, and now Johanna watched Kupferdre's soldiers, many of them mutilated, every single one of them humiliated. Under the terms of the surrender, Germany was obliged to pay reparations, which undermined the economy and accelerated hyperinflation; in 1924, Johanna's beloved Ruhr was again occupied by the French, who "stole" German coal as punishment for unpaid reparations. Her parents had lost their savings and she was looking for work and was penniless. In 1924, Johanna married a miner named Wilhelm Langefeld, who died of lung disease two years later.

Here Johanna’s “odyssey” was interrupted; she “vanished into the years,” Margaret wrote. The mid-twenties were a dark period that faded from her memory except for her reported affair with another man, which left her pregnant and dependent on Protestant charity groups.

While Langefeld and millions like her struggled to survive, other German women found freedom in the twenties. The socialist-led Weimar Republic accepted financial assistance from America, was able to stabilize the country and follow a new liberal course. German women gained the right to vote and, for the first time in history, joined political parties, especially those of the left. Imitating Rosa Luxemburg, leader of the communist Spartacus movement, middle-class girls (including Margarete Buber-Neumann) cut their hair, watched Bertolt Brecht plays, wandered through the woods and chatted about the revolution with comrades from the Wandervogel communist youth group. Meanwhile, working-class women across the country raised money for Red Aid, joined unions and went on strike at factory gates.

In Munich in 1922, when Adolf Hitler blamed Germany's woes on an "overweight Jew," a precocious Jewish girl named Olga Benario ran away from home to join a communist cell, abandoning her comfortable middle-class parents. She was fourteen years old. A few months later, the dark-eyed schoolgirl was already leading her comrades along the paths of the Bavarian Alps, swimming in mountain streams, and then reading Marx with them by the fire and planning the German communist revolution. In 1928, she rose to fame by attacking a Berlin courthouse and freeing a German communist who was facing the guillotine. In 1929, Olga left Germany for Moscow to train with Stalin's elite before leaving to start a revolution in Brazil.

Olga Benario. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Olga Benario. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, in the impoverished Ruhr valley, Johanna Langefeld was already a single mother with no hope for the future. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered a worldwide depression that plunged Germany into a new and deeper economic crisis, throwing millions out of work and causing widespread discontent. Langefeld's greatest fear was that her son Herbert would be taken away from her if she fell into poverty. But instead of joining the poor, she decided to help them by turning to God. It was her religious beliefs that motivated her to work with the poorest of the poor, as she told Margaret at her kitchen table in Frankfurt all these years later. She found work in social services, where she taught home economics to unemployed women and “rehabilitated prostitutes.”

In 1933, Johanna Langefeld found a new savior in Adolf Hitler. Hitler's program for women could not have been simpler: German women were to stay at home, bear as many Aryan children as possible, and submit to their husbands. Women were not suited to public life; Most jobs would be unavailable to women, and their ability to attend university would be limited.

Such sentiments were easy to find in any European country of the 1930s, but the Nazis' language towards women was unique in its offensiveness. Hitler's entourage not only spoke with open contempt about the "stupid", "inferior" female sex - they again and again demanded "segregation" between men and women, as if men did not see any purpose in women at all, except as a pleasant decoration and, of course, source of offspring. Jews were not Hitler's only scapegoats for Germany's woes: women emancipated during the Weimar Republic were accused of stealing jobs from men and corrupting national morals.

And yet Hitler was able to charm millions of German women who wanted the “man with an iron grip” to restore pride and faith in the Reich. Crowds of such supporters, many of them deeply religious and inflamed by Joseph Goebbels's anti-Semitic propaganda, attended the Nuremberg rally to celebrate the Nazi victory in 1933, where American reporter William Shirer mingled with the crowd. “Hitler rode into this medieval city at sunset today, past slender phalanxes of jubilant Nazis... Tens of thousands of swastika flags obscure the Gothic landscape of the place...” Later that evening, outside the hotel where Hitler was staying: “I was slightly shocked by the sight of the faces, especially the faces of women... They looked at him as if he were the Messiah..."

There is no doubt that Langefeld cast her vote for Hitler. She longed for revenge for the humiliation of her country. And she liked the idea of “respect for family” that Hitler spoke about. She also had personal reasons to be grateful to the regime: for the first time, she had a stable job. For women - and even more so for single mothers - most career paths were closed, except for the one Lengefeld chose. She was transferred from the social security service to the prison service. In 1935 she was promoted again to head a penal colony for prostitutes in Brauweiler, near Cologne.

In Brauweiler it began to seem that she did not so completely share the Nazi methods of helping the “poorest of the poor.” In July 1933, a law was passed to prevent the birth of offspring with hereditary diseases. Sterilization became a way to deal with weaklings, slackers, criminals and crazy people. The Fuhrer was sure that all these degenerates were leeches of the state treasury, they should be deprived of offspring in order to strengthen Volksgemeinschaft- a community of purebred Germans. In 1936, Brauweiler's head, Albert Bose, stated that 95% of his female prisoners were "incapable of improvement and should be sterilized for moral reasons and the desire to create a healthy Volk."

In 1937, Bose fired Langefeld. Brauweiler's records indicate that she was fired for theft, but in fact it was because of her struggle with such methods. The records also say that Langefeld still has not joined the party, although it was mandatory for all workers.

The idea of “respect” for family did not convince Lina Hug, the wife of a member of the Communist parliament in Wüttenberg. On January 30, 1933, when she heard that Hitler had been elected chancellor, it became clear to her that the new security service, the Gestapo, would come for her husband: “At meetings we warned everyone about the danger of Hitler. They thought that people would go against him. We were wrong".

And so it happened. On January 31 at 5 am, while Lina and her husband were still sleeping, Gestapo thugs showed up to them. The recount of the Reds has begun. “Helmets, revolvers, batons. They walked around in clean linen with obvious pleasure. We were not strangers at all: we knew them, and they knew us. They were grown men, fellow citizens - neighbors, fathers. Ordinary people. But they pointed loaded pistols at us, and in their eyes there was only hatred.”

Lina's husband began to get dressed. Lina was surprised how he managed to put on his coat so quickly. Will he leave without saying a word?

What are you doing? - she asked.

“What can you do,” he said and shrugged.

- He's a member of parliament! - she shouted to the police armed with batons. They laughed.

- Did you hear? Commie, that's what you are. But we will cleanse this infection from you.

While the father of the family was being escorted, Lina tried to drag their screaming ten-year-old daughter Katie away from the window.

“I don’t think people will put up with this,” said Lina.

Four weeks later, on February 27, 1933, while Hitler was trying to seize power in the party, someone set fire to the German parliament, the Reichstag. They blamed the communists, although many assumed that the Nazis were behind the arson, looking for a reason to intimidate political opponents. Hitler immediately issued an order for “preventive detention”; now anyone could be arrested for “treason.” Just ten miles from Munich, a new camp for such “traitors” was being prepared to open.

The first concentration camp, Dachau, opened on March 22, 1933. In the following weeks and months, Hitler's police sought out every communist, even a potential one, and brought them to where their spirit was to be broken. The Social Democrats faced the same fate as members of trade unions and all other “enemies of the state.”

There were Jews in Dachau, especially among the communists, but they were few in number - Jews were not arrested in huge numbers in the early years of Nazi rule. Those in the camps at that time were arrested for resistance to Hitler, and not for their race. At first, the main purpose of the concentration camps was to suppress resistance within the country, and after that other goals could be taken on. The person most suitable for this task was responsible for the suppression - Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, who soon also became head of the police, including the Gestapo.

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was not your average police chief. He was a short, thin man with a weak chin and gold-rimmed glasses on his pointed nose. Born on October 7, 1900, he was the middle child in the family of Gebhard Himmler, assistant director of a school near Munich. He spent the evenings in their cozy Munich apartment, helping Himmler Sr. with his stamp collection or listening to the heroic adventures of his military grandfather, while the charming mother of the family, a devout Catholic, embroidered, sitting in the corner.

Young Henry was an excellent student, but other students considered him a cram and often bullied him. In physical education, he could barely reach the parallel bars, so the teacher forced him to do painful squats while his classmates cheered. Years later, in a men's concentration camp, Himmler invented a new torture: prisoners were chained in a circle and forced to jump and squat until they fell. And then they were beaten to make sure they wouldn’t get up.

After leaving school, Himmler dreamed of joining the army and even served as a cadet, but poor health and eyesight prevented him from becoming an officer. Instead, he studied agriculture and raised chickens. He was consumed by another romantic dream. He returned to his homeland. In his free time, he walked through his beloved Alps, often with his mother, or studied astrology and genealogy, along the way making notes in a diary about every detail in his life. “Thoughts and worries still won’t leave my head,” he complains.

By the age of twenty, Himmler constantly berated himself for not conforming to social and sexual norms. “I’m always babbling,” he wrote, and when it came to sex: “I don’t let myself say a word.” By the 1920s he had joined the Munich men's Thule Society, where the origins of Aryan supremacy and the Jewish threat were discussed. He was also accepted into the Munich far-right wing of parliamentarians. “It’s so good to put on the uniform again,” he noted. The National Socialists (Nazis) began to talk about him: “Henry will fix everything.” His organizational skills and attention to detail were second to none. He also showed that he could predict Hitler's wishes. As Himmler discovered, it is very useful to be “cunning as a fox.”

In 1928 he married Margaret Boden, a nurse seven years his senior. They had a daughter, Gudrun. Himmler also succeeded in the professional sphere: in 1929 he was appointed head of the SS (at that time they were only engaged in protecting Hitler). By 1933, when Hitler came to power, Himmler had transformed the SS into an elite unit. One of his tasks was the management of concentration camps.

Hitler proposed the idea of concentration camps in which oppositionists could be collected and suppressed. As an example, he focused on British concentration camps during the South African War of 1899-1902. Himmler was responsible for the style of the Nazi camps; he personally chose the site for the prototype in Dachau and its commandant, Theodor Eicke. Subsequently, Eicke became the commander of the “Death's Head” unit - the so-called concentration camp guard units; its members wore a skull and crossbones badge on their caps, showing their kinship with death. Himmler ordered Eicke to develop a plan to crush all "enemies of the state."

This is exactly what Eicke did in Dachau: he created an SS school, the students called him “Papa Eicke”, he “tempered” them before sending them to other camps. Hardening meant that students should be able to hide their weakness in front of enemies and “show only a grin” or, in other words, be able to hate. Among Eicke's first recruits was Max Kögel, the future commandant of Ravensbrück. He came to Dachau in search of work - he was imprisoned for theft and only recently got out.

Kögel was born in the south of Bavaria, in the mountain town of Füssen, which is famous for its lutes and Gothic castles. Kögel was the son of a shepherd and was orphaned at the age of 12. As a teenager, he herded cattle in the Alps until he began looking for work in Munich and became involved in the far-right "people's movement." In 1932 he joined the Nazi Party. “Papa Eike” quickly found a use for the thirty-eight-year-old Koegel, because he was already a man of the strongest temperament.

In Dachau, Kögel also served with other SS men, for example, with Rudolf Höss, another recruit, the future commandant of Auschwitz, who managed to serve in Ravensbrück. Subsequently, Höss fondly recalled his days in Dachau, talking about SS personnel who deeply fell in love with Eicke and forever remembered his rules, which “remained with them forever in their flesh and blood.”

Eicke's success was so great that soon several more camps were built based on the Dachau model. But in those years, neither Eicke, nor Himmler, nor anyone else even thought about a concentration camp for women. The women who fought Hitler were simply not seen as a serious threat.

Thousands of women came under Hitler's repression. During the Weimar Republic, many of them felt free: trade union members, doctors, teachers, journalists. Often they were communists or wives of communists. They were arrested and treated horribly, but not sent to camps like Dachau; I didn’t even think about opening a women’s department in the men’s camps. Instead, they were sent to women's prisons or colonies. The regime there was tough, but tolerant.

Many political prisoners were taken to Moringen, a labor camp near Hanover. 150 women slept in unlocked rooms while guards ran around buying wool for knitting on their behalf. Sewing machines rattled around the prison premises. The table of the “nobles” stood separately from the rest, behind which sat the senior members of the Reichstag and the wives of the factory owners.

However, as Himmler discovered, women can be tortured differently than men. The simple fact that the men were killed and the children taken - usually to Nazi orphanages - was painful enough. Censorship did not allow asking for help.

Barbara Führbringer tried to warn her American sister when she heard that her husband, a communist Reichstag member, had been tortured to death in Dachau and their children were placed in foster care by the Nazis:

Dear sister!

Unfortunately, things are going badly. My dear husband Theodor died suddenly in Dachau four months ago. Our three children were placed in a state charity home in Munich. I'm at a women's camp in Moringen. There's not a penny left in my account anymore.

The censors did not let her letter through, and she had to rewrite it:

Dear sister!

Unfortunately, things are not going as we would like. My dear husband Theodore died four months ago. Our three children live in Munich, at Brenner Strasse 27. I live in Moringen, near Hannover, at Breit Strasse 32. I would be very grateful if you could send me some money.

Himmler figured that if the men's collapse was sufficiently frightening, then everyone else would be forced to yield. The method paid off in many ways, as Lina Hug, who was arrested a few weeks after her husband and placed in another prison, noted: “Didn’t anyone see where this was going? Did no one see the truth behind the shameless demagoguery of Goebbels’s articles? I saw this even through the thick walls of the prison, while more and more people on the outside submitted to their demands.”

By 1936, the political opposition was completely destroyed, and the humanitarian units of the German churches began to support the regime. The German Red Cross sided with the Nazis; at all meetings, the Red Cross banner began to appear side by side with the swastika, and the guardian of the Geneva Conventions, the International Committee of the Red Cross, inspected Himmler's camps - or at least the model blocks - and gave the green light. Western countries perceived the existence of concentration camps and prisons as an internal matter of Germany, considering it not their business. In the mid-1930s, most Western leaders still believed that the greatest threat to the world came from communism, not Nazi Germany.

Despite the absence of significant opposition both at home and abroad, at the initial stage of his reign the Fuhrer closely monitored public opinion. In a speech given at an SS training camp, he noted: “I always know that I must never take a single step that could be reversed. You always need to feel the situation and ask yourself: “What can I give up at the moment, and what can’t I?”

Even the fight against German Jews proceeded much more slowly at first than many party members wanted. In the early years, Hitler passed laws to prevent Jews from working and living in public, fueling hatred and persecution, but he felt it would take some time before further steps were taken. Himmler also knew how to sense the situation.

In November 1936, the Reichsführer SS, who was not only the head of the SS but also the chief of police, had to deal with an international upheaval within the community of German communist women. His reason went off the ship in Hamburg straight into the hands of the Gestapo. She was eight months pregnant. Her name was Olga Benario. The long-legged girl from Munich, who had run away from home and become a communist, was now a 35-year-old woman on the verge of universal fame among the world's communists.

After studying in Moscow in the early 1930s, Olga was accepted into the Comintern and in 1935 Stalin sent her to Brazil to help coordinate a coup against President Getúlio Vargas. The operation was led by the legendary Brazilian rebel leader Luis Carlos Prestes. The rebellion was organized with the goal of bringing about a communist revolution in the largest country in South America, thereby providing Stalin with a foothold in the Western Hemisphere. However, with the help of information received from British intelligence, the plan was discovered, Olga was arrested along with another conspirator, Eliza Evert, and sent to Hitler as a “gift”.

From the Hamburg docks, Olga was transported to Berlin's Barminstrasse prison, where four weeks later she gave birth to a girl, Anita. Communists around the world launched a campaign to free them. The case attracted widespread attention, largely due to the fact that the child's father was the notorious Carlos Prestes, leader of the failed coup; they fell in love and got married in Brazil. Olga's courage and her dark but sophisticated beauty added poignancy to the story.

Such an unpleasant story was especially undesirable for publicity in the year of the Olympic Games in Berlin, when a lot was done to whiten the image of the country. (For example, before the start of the Olympics, a roundup was carried out on Berlin gypsies. In order to remove them from the public eye, they were herded into a huge camp built in a swamp in the Berlin suburb of Marzahn). The Gestapo chiefs attempted to defuse the situation by offering to release the child, handing him over to Olga's mother, the Jewish woman Eugenia Benario, who lived in Munich at the time, but Eugenia did not want to accept the child: she had long ago renounced her communist daughter and did the same most with my granddaughter. Himmler then gave Prestes' mother Leocadia permission to take Anita away, and in November 1937 the Brazilian grandmother took the child from Barminstrasse prison. Olga, deprived of her baby, was left alone in the cell.

In a letter to Leocadia, she explained that she did not have time to prepare for the separation:

“I’m sorry that Anita’s things are in such a state. Did you get her daily routine and weight chart? I tried my best to make a table. Are her internal organs okay? And the bones are her legs? She may have suffered due to the extraordinary circumstances of my pregnancy and her first year of life."

By 1936, the number of women in German prisons began to rise. Despite the fear, German women continued to operate underground; many were inspired by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Those sent to the Moringen women's "camp" in the mid-1930s included more communists and former members of the Reichstag, as well as women working in small groups or alone, such as the disabled artist Gerda Lissack, who created anti-Nazi leaflets. Ilse Gostinski, a young Jewish woman who typed articles critical of the Fuhrer, was arrested by mistake. The Gestapo was looking for her twin sister Jelse, but she was in Oslo organizing evacuation routes for Jewish children, so they took Ilse instead.

In 1936, 500 German housewives arrived in Moringen with Bibles and neat white headscarves. These women, Jehovah's Witnesses, protested when their husbands were drafted into the army. They declared that Hitler is the Antichrist, that God is the only ruler on Earth, not the Fuhrer. Their husbands and other male Jehovah's Witnesses were sent to Hitler's new camp called Buchenwald, where they received 25 lashes of a leather whip. But Himmler knew that even his SS men did not have the courage to flog German housewives, so in Moringen the warden, a kindly lame retired soldier, simply took the Bibles from Jehovah's Witnesses.

In 1937, the passage of a law against Rassenchande- literally, "racial desecration" - prohibiting relations between Jews and non-Jews, led to a further influx of Jewish women into Moringen. Later, in the second half of 1937, women prisoners in the camp noticed a sudden increase in the number of vagrants brought in already “limping; some with crutches, many coughing up blood.” In 1938 many prostitutes arrived.

Elsa Krug was working as usual when a group of Düsseldorf police officers arrived at 10 Corneliusstrasse and began banging on the door, screaming. It was 2 a.m. on July 30, 1938. Police raids had become commonplace, and Elsa had no reason to panic, although lately they had become more frequent. Prostitution, according to the laws of Nazi Germany, was legal, but the police had many excuses to act: perhaps one of the women had failed a syphilis test, or an officer needed a tip on yet another communist cell on the docks of Düsseldorf.

Several Düsseldorf officers knew these women personally. Elsa Krug was always in demand either because of the special services she provided - she was into sadomasochism - or because of gossip, and she always kept her ear to the ground. Elsa was also famous on the streets; She took the girls under her wing whenever possible, especially if the street child had just arrived in the city, because Elsa found herself on the streets of Düsseldorf in the same situation ten years ago - without work, far from home and penniless.

However, it soon turned out that the raid on July 30 was special. Frightened customers grabbed what they could and ran out into the street half naked. That same night, similar raids took place near the place where Agnes Petrie worked. Agnes's husband, a local pimp, was also captured. Having combed the block, the police detained a total of 24 prostitutes, and by six in the morning they were all behind bars, without information about their release.

The attitude towards them at the police station was also different. The officer on duty, Sergeant Paine, knew that most of the prostitutes spent the night in local cells more than once. Taking out a large, dark ledger, he recorded them in the usual manner, noting names, addresses, and personal effects. However, in the column entitled “reason for arrest,” Pinein carefully wrote, next to each name, “Asoziale,” “asocial type,” a word he had not used before. And at the end of the column, also for the first time, a red inscription appeared - “Transportation”.

In 1938, similar raids took place across Germany as the Nazi purges of the poor entered a new stage. The government launched the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Movement against Parasites) program, targeting those considered marginalized. This movement was not noticed by the rest of the world, it did not receive wide publicity in Germany, but more than 20 thousand so-called “asocials” - “tramps, prostitutes, parasites, beggars and thieves” - were caught and sent to concentration camps.

The outbreak of World War II was still a year away, but Germany's war against its own undesirable elements had already begun. The Führer said that in preparation for war the country must remain "pure and strong" and therefore "useless mouths" must be shut. With Hitler's rise to power, mass sterilization of the mentally ill and mentally retarded began. In 1936, the Roma were placed on reservations near major cities. In 1937, thousands of "hardened criminals" were sent to concentration camps without trial. Hitler approved of such measures, but the instigator of the persecution was the police chief and head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, who also called for sending “asocials” to concentration camps in 1938.

The timing mattered. Long before 1937, the camps, originally created to get rid of political opposition, began to empty. The communists, social democrats and others arrested in the early years of Himmler's rule were largely defeated and most returned home broken. Himmler, who opposed such mass liberation, saw that his department was in danger and began to look for new uses for the camps.

Before this, no one had seriously proposed using concentration camps for anything other than political opposition, and by filling them with criminals and the dregs of society, Himmler could revive his punitive empire. He considered himself more than just a police chief, his interest in science - in all kinds of experiments that could help create the perfect Aryan race - was always his main goal. By gathering "degenerates" within his camps, he secured a central role in the Fuehrer's most ambitious experiment to cleanse the German gene pool. In addition, the new prisoners were to become a ready workforce for the restoration of the Reich.

The nature and purpose of the concentration camps would now change. In parallel with the decrease in the number of German political prisoners, social renegades would appear in their place. Among those arrested - prostitutes, petty criminals, the poor - at first there were as many women as men.

A new generation of purpose-built concentration camps was now being created. And since Moringen and other women's prisons were already overcrowded and also costly, Himmler proposed building a concentration camp for women. In 1938, he convened his advisers to discuss a possible location. Apparently, Himmler's friend Gruppenführer Oswald Pohl proposed building a new camp in the Mecklenburg Lake District, near the village of Ravensbrück. Paul knew this area because he had a country house there.

Rudolf Hess later claimed to have warned Himmler that there would not be enough space: the number of women had to increase, especially after the start of the war. Others noted that the ground was swampy and construction of the camp would be delayed. Himmler brushed aside all objections. Just 80 km from Berlin, the location was convenient for inspections, and he often went there to visit Pohl or his childhood friend, the famous surgeon and SS man Karl Gebhardt, who was in charge of the Hohenlichen medical clinic just 8 km from the camp.

Himmler ordered the transfer of male prisoners from Berlin's Sachsenhausen concentration camp to the construction of Ravensbrück as quickly as possible. At the same time, the remaining prisoners from the men's concentration camp in Lichtenburg near Torgau, which was already half empty, were to be transferred to the Buchenwald camp, opened in July 1937. Women assigned to the new women's camp were to be kept in Lichtenburg during the construction of Ravensbrück.

Inside the barred carriage, Lina Haag had no idea where she was going. After four years in a prison cell, she and many others were told they were being "transported." Every few hours the train stopped at a station, but their names - Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Mannheim - meant nothing to her. Lina looked at the “ordinary people” on the platforms - she had not seen such a picture for years - and ordinary people looked at “these pale figures with sunken eyes and tangled hair.” At night, the women were removed from the train and transferred to local prisons. The female guards terrified Lina: “It was impossible to imagine that in the face of all this suffering they could gossip and laugh in the corridors. Most of them were virtuous, but this was a special kind of piety. They seemed to be hiding behind God, resisting their own baseness.”

We can all agree that the Nazis did terrible things during World War II. The Holocaust was perhaps their most famous crime. But terrible and inhuman things happened in the concentration camps that most people did not know about. Prisoners of the camps were used as test subjects in a variety of experiments, which were very painful and usually resulted in death.

Experiments with blood clotting

Dr. Sigmund Rascher conducted blood clotting experiments on prisoners in the Dachau concentration camp. He created a drug, Polygal, which included beets and apple pectin. He believed that these tablets could help stop bleeding from battle wounds or during surgery.

Each test subject was given a tablet of this drug and shot in the neck or chest to test its effectiveness. Then the prisoners' limbs were amputated without anesthesia. Dr. Rusher created a company to produce these pills, which also employed prisoners.

Experiments with sulfa drugs

In the Ravensbrück concentration camp, the effectiveness of sulfonamides (or sulfonamide drugs) was tested on prisoners. Subjects were given incisions on the outside of their calves. Doctors then rubbed a mixture of bacteria into the open wounds and stitched them up. To simulate combat situations, glass shards were also inserted into the wounds.

However, this method turned out to be too soft compared to the conditions at the fronts. To simulate gunshot wounds, blood vessels were ligated on both sides to stop blood circulation. The prisoners were then given sulfa drugs. Despite the advances made in the scientific and pharmaceutical fields due to these experiments, prisoners suffered terrible pain, which led to severe injury or even death.

Freezing and hypothermia experiments

The German armies were ill-prepared for the cold they faced on the Eastern Front, from which thousands of soldiers died. As a result, Dr. Sigmund Rascher conducted experiments in Birkenau, Auschwitz and Dachau to find out two things: the time required for body temperature to drop and death, and methods for reviving frozen people.

Naked prisoners were either placed in a barrel of ice water or forced outside in sub-zero temperatures. Most of the victims died. Those who had just lost consciousness were subjected to painful revival procedures. To revive the subjects, they were placed under sunlight lamps that burned their skin, forced to copulate with women, injected with boiling water, or placed in baths of warm water (which turned out to be the most effective method).

Experiments with incendiary bombs

For three months in 1943 and 1944, Buchenwald prisoners were tested on the effectiveness of pharmaceuticals against phosphorus burns caused by incendiary bombs. The test subjects were specially burned with the phosphorus composition from these bombs, which was a very painful procedure. Prisoners suffered serious injuries during these experiments.

Experiments with sea water

Experiments were carried out on prisoners at Dachau to find ways to turn sea water into drinking water. The subjects were divided into four groups, the members of which went without water, drank sea water, drank sea water treated according to the Burke method, and drank sea water without salt.

Subjects were given food and drink assigned to their group. Prisoners who received seawater of one kind or another eventually began to suffer from severe diarrhea, convulsions, hallucinations, went crazy and eventually died.

In addition, subjects underwent liver needle biopsies or lumbar punctures to collect data. These procedures were painful and in most cases resulted in death.

Experiments with poisons

At Buchenwald, experiments were conducted on the effects of poisons on people. In 1943, prisoners were secretly injected with poisons.

Some died themselves from poisoned food. Others were killed for the sake of dissection. A year later, prisoners were shot with bullets filled with poison to speed up the collection of data. These test subjects experienced terrible torture.

Experiments with sterilization

As part of the extermination of all non-Aryans, Nazi doctors conducted mass sterilization experiments on prisoners of various concentration camps in search of the least labor-intensive and cheapest method of sterilization.

In one series of experiments, a chemical irritant was injected into women's reproductive organs to block the fallopian tubes. Some women have died after this procedure. Other women were killed for autopsies.

In a number of other experiments, prisoners were exposed to strong X-rays, which resulted in severe burns on the abdomen, groin and buttocks. They were also left with incurable ulcers. Some test subjects died.

Experiments on bone, muscle and nerve regeneration and bone transplantation

For about a year, experiments were carried out on prisoners in Ravensbrück to regenerate bones, muscles and nerves. Nerve surgeries involved removing segments of nerves from the lower extremities.

Experiments with bones involved breaking and setting bones in several places on the lower limbs. The fractures were not allowed to heal properly because doctors needed to study the healing process as well as test different healing methods.

Doctors also removed many fragments of the tibia from test subjects to study bone tissue regeneration. Bone transplants included transplanting fragments of the left tibia onto the right and vice versa. These experiments caused unbearable pain and severe injuries to the prisoners.

Experiments with typhus

From the end of 1941 to the beginning of 1945, doctors carried out experiments on prisoners of Buchenwald and Natzweiler in the interests of the German armed forces. They tested vaccines against typhus and other diseases.

Approximately 75% of test subjects were injected with trial typhus vaccines or other chemicals. They were injected with the virus. As a result, more than 90% of them died.

The remaining 25% of experimental subjects were injected with the virus without any prior protection. Most of them did not survive. Doctors also conducted experiments related to yellow fever, smallpox, typhoid, and other diseases. Hundreds of prisoners died, and many more suffered unbearable pain as a result.

Twin experiments and genetic experiments

The goal of the Holocaust was the elimination of all people of non-Aryan origin. Jews, blacks, Hispanics, homosexuals and other people who did not meet certain requirements were to be exterminated so that only the "superior" Aryan race remained. Genetic experiments were carried out to provide the Nazi Party with scientific evidence of Aryan superiority.

Dr. Josef Mengele (also known as the "Angel of Death") was greatly interested in twins. He separated them from the rest of the prisoners upon their arrival at Auschwitz. Every day the twins had to donate blood. The actual purpose of this procedure is unknown.

Experiments with twins were extensive. They had to be carefully examined and every inch of their body measured. Comparisons were then made to determine hereditary traits. Sometimes doctors performed massive blood transfusions from one twin to the other.

Since people of Aryan origin mostly had blue eyes, experiments were done with chemical drops or injections into the iris to create them. These procedures were very painful and led to infections and even blindness.

Injections and lumbar punctures were done without anesthesia. One twin was specifically infected with the disease, and the other was not. If one twin died, the other twin was killed and studied for comparison.

Amputations and organ removals were also performed without anesthesia. Most twins who ended up in concentration camps died in one way or another, and their autopsies were the last experiments.

Experiments with high altitudes

From March to August 1942, prisoners of the Dachau concentration camp were used as test subjects in experiments to test human endurance at high altitudes. The results of these experiments were supposed to help the German air force.

The test subjects were placed in a low-pressure chamber in which atmospheric conditions were created at altitudes of up to 21,000 meters. Most of the test subjects died, and the survivors suffered from various injuries from being at high altitudes.

Experiments with malaria

For more than three years, more than 1,000 Dachau prisoners were used in a series of experiments related to the search for a cure for malaria. Healthy prisoners became infected with mosquitoes or extracts from these mosquitoes.

Prisoners who fell ill with malaria were then treated with various drugs to test their effectiveness. Many prisoners died. The surviving prisoners suffered greatly and basically became disabled for the rest of their lives.

An 18-year-old Soviet girl is extremely exhausted. The photo was taken during the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp in 1945. This is the first German concentration camp, founded on March 22, 1933, near Munich (a city on the Isar River in southern Germany). It housed more than 200 thousand prisoners, according to official data, of which 31,591 prisoners died from disease, malnutrition or committed suicide. The conditions were so terrible that hundreds of people died here every week.

This photo was taken between 1941 and 1943 by the Paris Holocaust Memorial. This shows a German soldier taking aim at a Ukrainian Jew during a mass execution in Vinnitsa (a city located on the banks of the Southern Bug, 199 kilometers southwest of Kyiv). On the back of the photo it was written: “The last Jew of Vinnitsa.”

This photo was taken between 1941 and 1943 by the Paris Holocaust Memorial. This shows a German soldier taking aim at a Ukrainian Jew during a mass execution in Vinnitsa (a city located on the banks of the Southern Bug, 199 kilometers southwest of Kyiv). On the back of the photo it was written: “The last Jew of Vinnitsa.”

The Holocaust was the persecution and mass extermination of Jews living in Germany during World War II, from 1933 to 1945.

German soldiers interrogate Jews after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943. Thousands of people died from disease and starvation in the overcrowded Warsaw ghetto, where the Germans herded more than 3 million Polish Jews back in October 1940.

German soldiers interrogate Jews after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943. Thousands of people died from disease and starvation in the overcrowded Warsaw ghetto, where the Germans herded more than 3 million Polish Jews back in October 1940.

The uprising against the Nazi occupation of Europe in the Warsaw Ghetto took place on April 19, 1943. During this riot, approximately 7,000 ghetto defenders were killed and approximately 6,000 were burned alive as a result of massive burning of buildings by German troops. The surviving residents, about 15 thousand people, were sent to the Treblinka death camp. On May 16 of the same year, the ghetto was finally liquidated.

The Treblinka death camp was established by the Nazis in occupied Poland, 80 kilometers northeast of Warsaw. During the existence of the camp (from July 22, 1942 to October 1943), about 800 thousand people died in it.

To preserve the memory of the tragic events of the 20th century, international public figure Vyacheslav Kantor founded and headed the World Holocaust Forum.

1943 A man takes the bodies of two Jews from the Warsaw ghetto. Every morning, several dozen corpses were removed from the streets. The bodies of Jews who died of starvation were burned in deep pits.

1943 A man takes the bodies of two Jews from the Warsaw ghetto. Every morning, several dozen corpses were removed from the streets. The bodies of Jews who died of starvation were burned in deep pits.

The officially established food standards for the ghetto were designed to allow the inhabitants to die from starvation. In the second half of 1941, the food standard for Jews was 184 kilocalories.

On October 16, 1940, Governor General Hans Frank decided to organize a ghetto, during which the population decreased from 450 thousand to 37 thousand people. The Nazis argued that Jews were carriers of infectious diseases and that isolating them would help protect the rest of the population from epidemics.

On April 19, 1943, German soldiers escort a group of Jews, including small children, into the Warsaw ghetto. This photograph was included in SS Gruppenführer Stroop's report to his military commander and was used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials in 1945.

On April 19, 1943, German soldiers escort a group of Jews, including small children, into the Warsaw ghetto. This photograph was included in SS Gruppenführer Stroop's report to his military commander and was used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials in 1945.

After the uprising, the Warsaw ghetto was liquidated. 7 thousand (out of more than 56 thousand) captured Jews were shot, the rest were transported to death camps or concentration camps. The photo shows the ruins of a ghetto destroyed by SS soldiers. The Warsaw ghetto lasted for several years, and during this time 300 thousand Polish Jews died there.

After the uprising, the Warsaw ghetto was liquidated. 7 thousand (out of more than 56 thousand) captured Jews were shot, the rest were transported to death camps or concentration camps. The photo shows the ruins of a ghetto destroyed by SS soldiers. The Warsaw ghetto lasted for several years, and during this time 300 thousand Polish Jews died there.

In the second half of 1941, the food standard for Jews was 184 kilocalories.

Mass execution of Jews in Mizoche (urban-type settlement, center of the Mizochsky village council of the Zdolbunovsky district, Rivne region of Ukraine), Ukrainian SSR. In October 1942, the residents of Mizoch opposed Ukrainian auxiliary units and German policemen who intended to liquidate the ghetto population. Photo courtesy of the Paris Holocaust Memorial.

Mass execution of Jews in Mizoche (urban-type settlement, center of the Mizochsky village council of the Zdolbunovsky district, Rivne region of Ukraine), Ukrainian SSR. In October 1942, the residents of Mizoch opposed Ukrainian auxiliary units and German policemen who intended to liquidate the ghetto population. Photo courtesy of the Paris Holocaust Memorial.

Deported Jews in the Drancy transit camp, on their way to a German concentration camp, 1942. In July 1942, French police herded more than 13 thousand Jews (including more than 4 thousand children) to the Vel d'Hiv winter velodrome in southwestern Paris, and then sent them to the train terminal in Drancy, northeast of Paris. Paris and deported to the east. Almost no one returned home...

Deported Jews in the Drancy transit camp, on their way to a German concentration camp, 1942. In July 1942, French police herded more than 13 thousand Jews (including more than 4 thousand children) to the Vel d'Hiv winter velodrome in southwestern Paris, and then sent them to the train terminal in Drancy, northeast of Paris. Paris and deported to the east. Almost no one returned home...

Drancy was a Nazi concentration camp and transit point that existed from 1941 to 1944 in France, used to temporarily hold Jews who were later sent to death camps.

This photo is courtesy of the Anne Frank House Museum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. It depicts Anne Frank, who in August 1944, along with her family and others, was hiding from the German occupiers. Later, everyone was captured and sent to prisons and concentration camps. Anna died of typhus at Bergen-Belsen (a Nazi concentration camp in Lower Saxony, located a mile from the village of Belsen and a few miles southwest of Bergen) at the age of 15. After the posthumous publication of her diary, Frank became a symbol of all Jews killed during World War II.

This photo is courtesy of the Anne Frank House Museum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. It depicts Anne Frank, who in August 1944, along with her family and others, was hiding from the German occupiers. Later, everyone was captured and sent to prisons and concentration camps. Anna died of typhus at Bergen-Belsen (a Nazi concentration camp in Lower Saxony, located a mile from the village of Belsen and a few miles southwest of Bergen) at the age of 15. After the posthumous publication of her diary, Frank became a symbol of all Jews killed during World War II.

Arrival of a trainload of Jews from Carpathian Ruthenia at the Auschwitz II extermination camp, also known as Birkenau, in Poland, May 1939.

Arrival of a trainload of Jews from Carpathian Ruthenia at the Auschwitz II extermination camp, also known as Birkenau, in Poland, May 1939.